In this very street, a building plot is formed by subdividing a garden on the private side of the road. If you were a planner, what restrictions would you think should be placed on the design of this soon-to-be-built house? In this context, it’s hard to make out coherent arguments for restrictions at all, other than the usual ones protecting the privacy of the neighbours.

But when were planners ever coherent? I write about this conundrum because last week I was looking at just such a building plot in a village nearby and the planners had peppered it with so many dos and don’ts that I walked away. In fact, it brought on a right grumpfest, which I can only dissipate by sharing it with you.

You see, as far as the planners were concerned, this was no ordinary building plot because the garden from which it was formed belonged to the nicest thatched cottage on the street and, at some point in the past 30 or 40 years, this cottage had been listed. Now if you list a house, you also list its outbuildings and its garden — what the planners refer to as the curtilage. And even if you separate a building plot off from the rest of the garden with a head-high brick wall and give it an entirely separate access, the building plot remains within the curtilage and you have, in effect, to build a new listed building.

So what should such a new house look like? A very good question and one that draws us right to the heart of the absurdities of contemporary planning. A new thatched cottage perhaps? No, that would be pastiche. A brick bungalow with a few tasteful adornments? Certainly not. Perhaps a variation on the 50s council housing stock, which itself was loosely based on the house types that Raymond Unwin developed in Letchworth, many of which are now listed. I don’t think so. No, what the planners would seem to want here is something a little bit cutting-edge contemporary, something that Kevin McLoud would feel happy to wander through on the next-but-one series of Grand Designs.

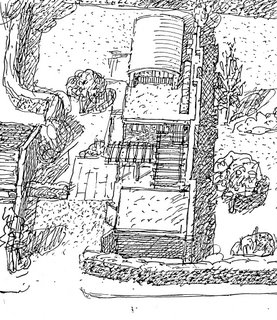

The applicants picked up on this and hired some architects to draw up something suitable. The plot is being offered with detailed planning permission for a very “contemporary” house. There is a curved metal roof over the main part of the house, some large glazed panels, some turf roofing and lots of oak cladding. Whether it actually works as a home is open to doubt – it only has three bedrooms for a start which is pretty light for a 240m2 house — but the planners obviously liked it because it has been approved and the plot is being marketed as if this was the house that had to be built on it. But they didn’t like it enough just to leave it at that. No, the planning permission comes with a long list of conditions, all stemming from the fact that this is a curtilage plot.

The applicants picked up on this and hired some architects to draw up something suitable. The plot is being offered with detailed planning permission for a very “contemporary” house. There is a curved metal roof over the main part of the house, some large glazed panels, some turf roofing and lots of oak cladding. Whether it actually works as a home is open to doubt – it only has three bedrooms for a start which is pretty light for a 240m2 house — but the planners obviously liked it because it has been approved and the plot is being marketed as if this was the house that had to be built on it. But they didn’t like it enough just to leave it at that. No, the planning permission comes with a long list of conditions, all stemming from the fact that this is a curtilage plot. Take the oak cladding. Why oak rather than any other timber, I have no idea, but the architects specified oak on the drawings. The planners responded by saying “Fine but we want to see just how it will look in practice.” So the cladding will have to be presented to them beforehand so they can judge its suitability. The brickwork also has to pass muster, not just the choice of brick but the bonding patterns and the coping details as well. Details of the gutters and downpipes have to be agreed: “no ghastly plastic here please.” It goes on and on. Materials used for the hard landscaping surfaces also have to be examined and agreed upon beforehand.

Can you believe that? They actually have the right to tell you what style of paving you can use? What difference can that possibly make to the thatched cottage next door, soon to be hidden behind a six-foot wall?

The planting is also subject to a whole raft of controls, some of them contradictory. For instance, the planners wish to maintain the hedge that currently separates the plot from the road, whilst highways are insisting on 2-metre visibility splays either side of the entrance. As the plot frontage is just 15 metres, it’s hard to see more than about 6 metres of hedge left standing after the opening is completed.

Condition 11 states: “No development shall take place until there has been submitted to and approved in writing by the Local Planning Authority a scheme of hard and soft landscaping, which shall include indications of all existing trees and hedgerows on the land, and details of any to be retained, together with measures for their protection in the course of development and specification of all proposed trees, hedges and shrub planting, which shall include details of species, density and size of stock.” I know this reads like gobble-de-gook – you read it three times and still can’t understand what it means – but what they are driving at is that they control what you can and can’t plant in the garden.

The subsequent Condition 12 seeks to place a time limit on all of this activity. Everything has to be done within the first planting season following occupation, though quite what recourse they would have if you didn’t do it on time I don’t know.

The reason for these conditions is stated: “To enhance the quality of the development and to assimilate it within the area.” Now this is where it gets really bizarre. It’s this word assimilate that gets me. Assimilate to what exactly? Because the one thing a modern-style house will do in this street is stick out. In fact, the planners want it to stick out, they would like it to win an award and to bask in the reflective glory.

What the planners really want is something built in good taste, but they can’t possibly say that because they would be laughed out of court on grounds of snobbery and elitism. So, in the New Labour world of spin that we now all inhabit, they simply change the meaning of an existing word so that it fits their agenda.

I showed the conditions to my wife, the gardener. “I’m not having them tell me what I can and can’t plant.” That was her gut reaction. Mine too.

No comments:

Post a Comment